Active Reinforcement Learning with Monte-Carlo Tree Search

Exploring Active Reinforcement Learning: Unveiling Insights from Monte-Carlo Tree Search and Sample-Based Search

As an applied data scientist collaborating with Dr. Ofra Amir at The Technion, I recently delved into the realm of active reinforcement learning, focusing on the intriguing challenges posed by a two-arm bandit configuration.

Some preliminaries

Understanding the Two-Arm Bandit Configuration

In the landscape of decision-making under uncertainty, the two-arm bandit problem stands as a classic model. In this configuration, an agent is faced with two options or “arms,” each associated with an unknown probability distribution of rewards. The challenge lies in selecting arms strategically over time to maximize cumulative rewards, balancing the exploration of uncertain options with the exploitation of known lucrative choices.

The Essence of Reinforcement Learning

Reinforcement learning (RL) is a paradigm in machine learning where an agent learns to make decisions by interacting with an environment. The goal is to discover an optimal policy that dictates the agent’s actions to maximize cumulative rewards over time. This involves navigating a trade-off between exploration (trying new actions to gather information) and exploitation (choosing actions that are currently deemed optimal based on existing knowledge).

Bridging Gaps with Active Reinforcement Learning

While traditional RL assumes full visibility of rewards and system dynamics, active reinforcement learning introduces a layer of realism by acknowledging that acquiring information comes at a cost. In this context, the agent must not only learn an optimal policy but also decide when and where to gather information about the environment. Active RL seeks to address the challenge of balancing exploration and exploitation in scenarios where the agent must actively query the environment to uncover crucial information, adding a dynamic layer to the learning process.

Finaly - The Problem’s Setup

In this dynamic setting, rewards remain veiled behind a querying cost, and the parameters of the transition function are shrouded in uncertainty. Drawing inspiration from two seminal papers—Active Reinforcement Learning with Monte-Carlo Tree Search and Efficient Bayes-Adaptive Reinforcement Learning using Sample-Based Search — our primary goal was to uncover (sub)optimal policies in this complex environment. To accomplish this, we pitted the BAMCPP algorithm from the aforementioned papers against the knowledge gradient algorithm (KD), specifically tailored to the querying setting. Surprisingly, initial comparisons showed that BAMCPP did not outperform KD. Undeterred, we embarked on refining the BAMCPP algorithm by introducing a temperature element into its Monte-Carlo Tree Search’s argmax stage, aiming to enhance its performance and reveal new insights into active reinforcement learning dynamics.

For simplicity, we looked at a two-armed bandit with Bernoulli distribution over its arms, p=0.2 for the “left” arm and p=0.8 for the “right” arm. The algorithms were tested against two cost functions which will be explained in the next section.

Exploring Alternatives: Knowledge Gradient and Mind-Changing-Cost-Heuristic

In our quest to unravel the mysteries of active reinforcement learning within the two-arm bandit framework, we delved into two alternative algorithms previously explored by Dr. Ofra’s MSc. student: Knowledge Gradient (KD) and Mind-Changing-Cost-Heuristic. Knowledge Gradient (KD) is a widely used approach that quantifies the expected improvement in the objective function given the current state of knowledge. It strikes a balance between exploration and exploitation by guiding the agent to query the environment at locations where information gain is maximized. On the other hand, the Mind-Changing-Cost-Heuristic introduces a unique perspective by considering the cost associated with changing one’s mind. This cost-aware approach recognizes that altering decisions based on new information comes with a price and aims to optimize the learning process by factoring in the cognitive overhead associated with mind-changing decisions. Both algorithms bring distinct methodologies to the table, contributing to the diverse landscape of strategies employed in active reinforcement learning.

Unraveling the Dynamics: BAMCPP and Knowledge Gradient Face-off

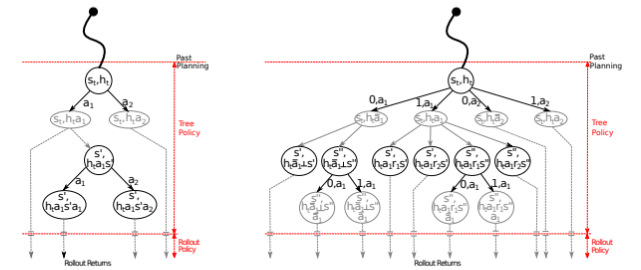

Our research delved into the active reinforcement learning arena, with a particular focus on assessing the efficacy of the Bayes-Adaptive Reinforcement Learning using Sample-Based Search (BAMCPP) algorithm in comparison to the well-established Knowledge Gradient (KD). BAMCPP, a method employing Bayesian learning and Monte Carlo tree search, introduces a unique blend of probabilistic reasoning and strategic decision-making. In the context of our study, the agent utilizes Monte Carlo tree search to not only select which arm to pull but also to determine whether to query the environment. Through simulations, the agent accumulates rewards, updating its beliefs about the arms’ reward distributions. Both KD and BAMCPP underwent rigorous testing within a fixed-cost environment (cost = 0.5) and a dynamic cost environment, where costs followed a policy incorporating factors such as query decisions, cost increases, and cost decreases. The dynamic cost policy, defined as:

cost=1⋅is_query⋅increase_factor+(1−1⋅is_query)⋅max(cost,decrease_factor⋅cost,base_cost)

provided a nuanced perspective on the algorithms’ adaptability in response to varying cost scenarios, with a base cost of 1, an increase factor of 2, and a decrease factor of 0.5.

Our research unfolded in two distinct stages, each contributing valuable insights to the realm of active reinforcement learning. In the initial phase, we applied the BAMCPP algorithm to our carefully crafted settings, meticulously comparing its performance against the benchmark set by Knowledge Gradient. This comparative analysis aimed to discern the algorithm’s strengths and weaknesses within the dynamic landscape of the two-arm bandit configuration with querying costs.

The second stage of our research initially envisioned designing a realistic cost function, deviating from a fixed cost structure to better mirror human decision-making processes. However, as the initial results did not align with our expectations, we pivoted our focus to the iterative improvement of the BAMCPP algorithm itself. This shift in strategy underscored our commitment to enhancing the algorithm’s efficacy, pushing the boundaries of its capabilities to potentially outperform existing state-of-the-art solutions. By navigating this iterative path, our research aimed not only to understand the nuances of active reinforcement learning in complex settings but also to actively contribute to the ongoing evolution of algorithms that tackle real-world decision-making challenges.

Assessing Performance: Metrics and Insights

- Reward:

- Definition: The average accumulated reward gained by each algorithm.

- Evaluation: Calculated by averaging over 100 runs/episodes.

Average Reward in a Chainging Cost setting for each method

- Regret:

- Definition: The average accumulated reward minus the query cost.

- Evaluation: Computed by subtracting the query cost from the average accumulated reward, with results averaged over 100 runs/episodes.

Average Regret in a Chainging Cost setting for each method

- Query Probability:

- Definition: The average probability of querying at each timestep over 100 runs.

- Evaluation: Provides insights into the algorithms’ decision-making dynamics, reflecting their tendency to actively seek information.

Query Probability in a Chainging Cost setting for each method

- Arms Convergence:

- Definition: The probability of each algorithm converging towards the higher-paid arm.

- Evaluation: Offers a measure of the algorithms’ ability to identify and exploit the more lucrative option in the two-arm bandit configuration. Results are averaged over 100 runs, providing a robust assessment of convergence behavior.

Arm Convergence in a Chainging Cost setting for each method

Results Analysis

In our evaluation of the algorithms, a pivotal moment arose during the tests in the changing cost experiments, prompting the introduction of an improved version of BAMCPP. This enhancement featured a temperature-like hyper-parameter strategically designed to encourage more querying at the initial stages of decision-making. The methodology involved allowing regular Monte Carlo Tree Search (MCTS) to unfold, but when selecting the current argmax over the arms and deciding whether to query (after reaching the maximum number of simulations), we introduced a bias towards querying. This was achieved by dividing the Q-values of querying by the current timestep and dividing the Q-values of the non-querying action by the remaining timesteps until reaching the horizon. The newfound hyper-parameter, determining the proportion of timesteps biased in this manner, added a nuanced layer to the algorithm’s adaptability.

Surprisingly, across both fixed cost and changing cost scenarios, the consistent trend emerged, with Knowledge Gradient (KD) consistently outperforming the improved BAMCPP in terms of higher accumulated reward. This finding underscores the challenges in refining algorithms for active reinforcement learning within the intricate dynamics of a two-arm bandit configuration with querying costs.

Conclusions and Discussion

In concluding our exploration of active reinforcement learning within the challenging confines of a two-arm bandit configuration, it became evident that the original BAMCPP algorithm struggled to query sufficiently compared to its counterpart, KD. The introduction of the temperature element successfully nudged BAMCPP towards more active querying, yet it fell short of achieving greater or equal rewards compared to KD. Despite this, it showcased a notable advantage in terms of regret, consistently outperforming KD in all settings. However, when considering convergence to the preferred arm, KD maintained an edge by consistently converging in all episodes, while BAMCPP exhibited variability, dependent on hyperparameters and at the expense of other performance metrics.

The sensitivity of BAMCPP to hyperparameters became a noteworthy focal point, revealing intricate relationships between exploration constants, depth limits during MCTS, querying probabilities, and convergence outcomes. Notably, higher querying probabilities often correlated with better convergence toward the preferred arm. Our research underscores the complex nature of BAMCPP and the challenges in optimizing hyperparameters to achieve competitive performance.

In terms of our original objective—comparing the performances of two algorithms in the domain of active reinforcement learning—it became apparent that KD, a known algorithm, continued to outshine BAMCPP in most metrics. Despite BAMCPP’s incorporation of Bayesian learning and Monte Carlo tree search, KD consistently demonstrated superior performance. The introduction of the temperature element represented a strategic attempt to enhance BAMCPP’s querying behavior, yet further avenues for improvement remain unexplored. A potential future direction involves investigating the convergence of the Bayesian learner within BAMCPP, considering the possibility of halting MCTS usage once convergence is achieved, thus potentially mitigating some of the algorithm’s sensitivity to hyperparameters.